The Need for an Ontology of Art: Seeing Deeper Spiritual Meanings in Indo-Muslim Paintings

The Need for an Ontology of Art: Seeing Deeper Spiritual Meanings in Indo-Muslim Paintings

Western scholars looking through their particular art lens are missing the ontological and spiritual meanings and significance in the works of South Asian Muslim art, says Murad Khan Mumtaz, an assistant professor of art at Williams College in Williamstown, Mass.

Mumtaz, a U.S.-based Pakistani artist and researcher trained in the traditional practice of Indian miniature painting, spoke on Feb. 29 on “The Need for an Ontology of Art: Indo-Muslim Painting as a Case Study.” The talk was presented at Yale’s Loria Center as part of a graduate student-led series of Pre/Early Modern Forums at the Department of the History of Art at Yale University.

Mumtaz, the author of the publication “Faces of God: Images of Devotion in Indo-Muslim Painting, 1500–1800,” presented a series of works of Islamic art that represented a deeper significance when seen from the ontological hierarchies of faith: levels of existence from the lower levels of mortals to the upper levels of the divine.

Mumtaz detailed how Islamic art has been reduced and misrepresented as being an iconophobic tradition instead of being seen for “the polyvalence of its figural artworks made for Muslim audiences” that has “remained hidden in plain view.”

He noted that the cosmological meanings and the cultures of devotion and rituals — foreign to previous Western interpretations — would be clearly evident to South Asian viewers knowing of Islamic intellectual and religious histories.

Focusing on the Mughal period between 1526 to circa 1800, Mumtaz presented examples of works that reflected the visual and literal metaphors of devotion which were presented as an ontological hierarchy of creation.

The hierarchy of the world that is expressed in Islamic art is reflected in the levels of the archetypal human body which is presented “like a cosmic map divided into ontological regions depicting levels of existence.” The triangle of life depicted a clear map from the lowest levels to the highest: from “nothingness,” to the next level of “the corporeal world,” to “the world of imagination,” to “the world of spirits,” to finally the highest point of existence: “Being.”

Mumtaz contextualized artworks and showed how these cosmic levels are echoed in the works of Islamic art.

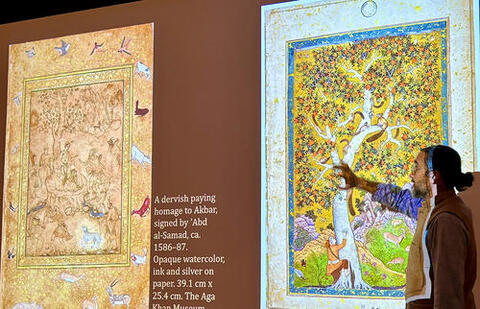

As examples, Mumtaz presented “Prince Salim with a falcon”, ca. 1600-1605, an opaque watercolor and gold on paper painting made during Emperor Akbar’s reign (R. 1555-1605) and in a work by Abu’l Hasan, (1589-c.1630) of “A Dervish Climbing the Tree of Life” (c. 1610) made for Emperor Jahangir (R. 1605-1627).

Such works as those by Hasan, said Mumtaz, have been principally viewed for their European influence and the canons of European art-making “with the supposition that the artist was merely following European themes and styles in which the artist was familiar from a young age. But here we have a problem of conflating stylistic elements with thematic elements.”

What that analysis overlooks is the greater cultural worldview, said Mumtaz, with Western scholars “at sea when attempting to locate artwork within the context of Islamic culture.”

This Western appraisal is one that fails to see nor understand its other-worldly allegories and its divine manifestations, he said, such as — in the Hasan work — a flattened gold sky, bold outlines of rock formations, and curiously giant-scaled squirrels.

Mumtaz said these “devotional markers” would be immediately identified and understood by Muslim viewers.

In the Hasan painting these markers also included its towering tree “representing the tree of life and sanctity,” a winding stream “dividing the realms of existence”, the images of angelic birds guarding its nest of eggs, to ultimately “a dreamlike sky representing heaven.”

Central to the Hasan work is the figure of the huntsman wearing local garb, presented as a seeker of truth, attempting the impossible task of scaling the tree, which acts as “an allegory of man’s spiritual task.”

“Once you start to see [the symbols], you see them everywhere [in South Asian art],” he said.

Mumtaz received his Ph.D in Art and Architectural History from the University of Virginia in 2018, his M.F.A. from Columbia University (2010) and his B.F.A. from the National College of Arts (2004).

The lecture received support from History of Art and Early Modern Studies at Yale University.

— Frank Rizzo