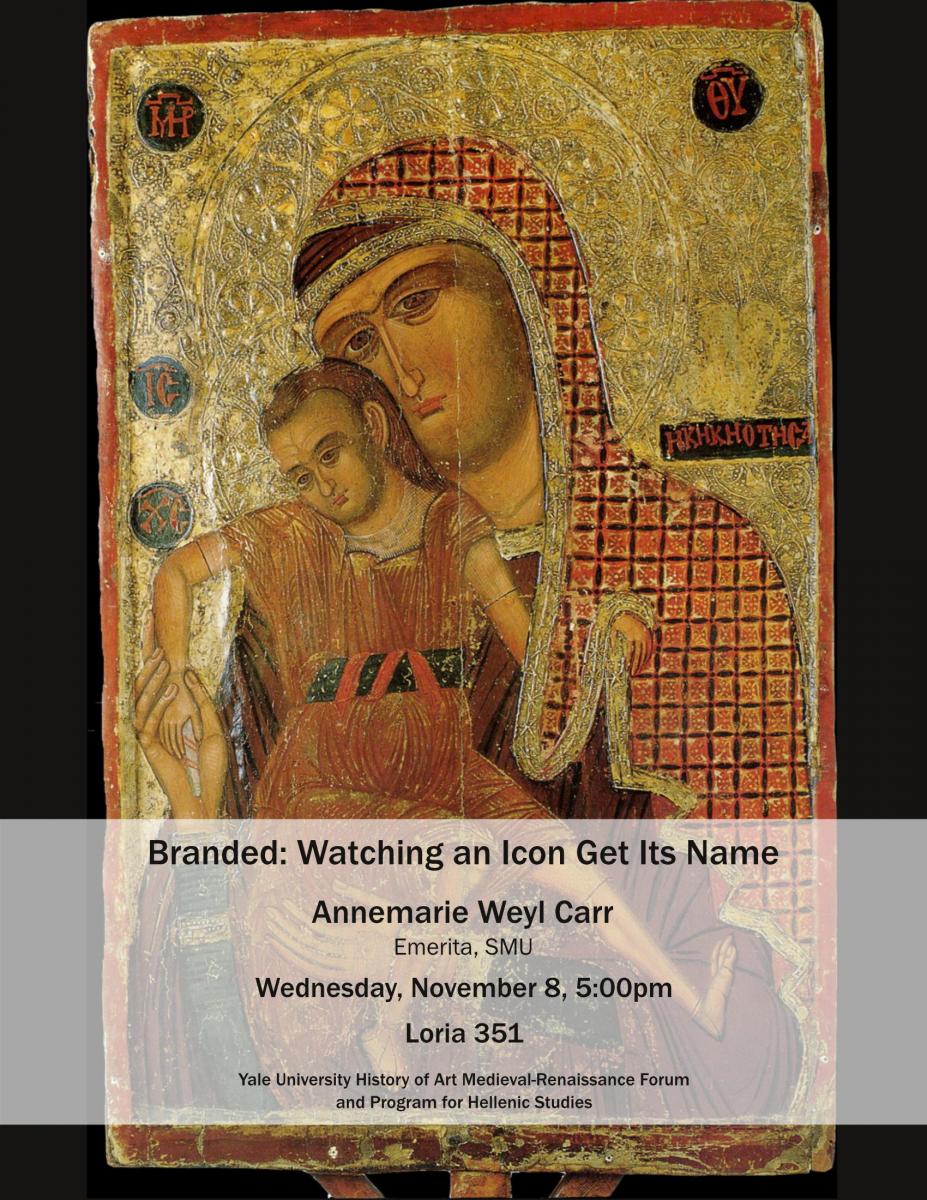

Med/Ren Colloquium: Annemarie Carr(SMU)

Branded: Watching an Icon Get Its Name

Annemarie Weyl Carr (acarr@smu.edu)

Few miracle-workers offer as much information about the incubation of their cults as does the icon of the Mother of God at Kykkos Monastery on Cyprus, known as the Kykkotissa. The Kykkotissa has a strong if subtly layered cult that is more in evidence today than it was when I began to study it two decades ago. I’ve been largely immersed in its early modern history, but have been drawn back recently to its beginning by some key attributional shifts. The emergence of a cult poses all kinds of questions—social, political, geographic, economic, religious, ethnic/creedal—and the Kykkotissa’s is no exception. Its study is strongly affected by the fact that emerged in the crusader centuries when Cyprus’ staunchly Orthodox populace was governed by French knights loyal to the Roman Church, its sense of special particularity is surely conditioned by Cyprus’ geography as an island; the icon’s legend is stuffed with sociological intimations. Often enough, the evidence yielded by such inquiries does service also for us art historians, who offer it as our own testimony. But there are art historical questions, too, and these need our attention. Since the Kykkotissa’s early evidence is visual, in its stream of replicas, attribution is clearly important, but so is seeing where in the evidentiary span the attributable replicas occur. That the legend’s content is interesting is fine, but first: what kinds of miraculous icons get legends? In what functional contexts do the replicas appear? What are they doing there? And of particular interest to me right now: what happens when an icon’s name gets attached to a replica? What is the difference between a replica with the name, and one without, especially in an island community where images’ identities were well -known? What happens when a name meaning “this icon, here” becomes “that icon, there”? I sense that there is a threshold here, not merely in the way the image is identified, but in the way it functions as an icon. Cult icons have histories not just as political or social forces, but also as sacred instruments. Close visual attention to the Kykkotissa’s rich early evidence may cast light on this evolution in icons’ work.